The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is auctioning the licensing rights for dozens of oil and gas blocks, opening up parts of the world’s second-largest rain forest to exploitation.

Why is the government doing this now?

Congolese leaders say they are seeking to generate revenue for the people of the DRC, which remains one of the five poorest countries in the world despite its spectacular natural resources. Congo’s development needs are not new, nor is speculation about the country’s oil and gas potential. The reserves up for auction are estimated to be worth over $600 billion. However, Greenpeace Africa says that communities living in the areas in question were not consulted by the government and residents doubt they will benefit from exploration.

More on:

Officials have also indicated that the timing relates to the global appetite for new sources of oil and gas to replace those lost in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and there is no doubt that countries with oil and gas reserves are finding enthusiastic suitors around the world.

But Congolese officials also want to remind the world just how consequential their choices are, and to prompt other countries, particularly wealthy ones, to act accordingly. The world needs climate solutions, and Kinshasa gains important leverage by reminding wealthy countries that it is in a position to greatly bolster or undermine plans to mitigate climate change. Too often, rich countries have offered insufficient funds to help poorer countries address their climate needs [PDF], and these contributions have materialized very slowly, or not at all. When support is available, it is often at the discretion of donors rather than Congolese officials. Making the point that the government can pursue alternative paths to those preferred by climate-conscious international partners could help motivate faster and more generous compensation and garner more respect for Congolese priorities when it comes to protecting the Congo Basin, which holds the world’s second-largest rain forest.

The DRC’s 2023 elections are another factor. The government can generate quick cash with the auction that can be used to deliver short-term wins to crucial constituencies, enhancing the electoral outlook for incumbents. A similar flurry of activity occurred before the last round of elections, though there has been little evidence of actual development.

More on:

What would be the consequences of oil and gas extraction in these areas?

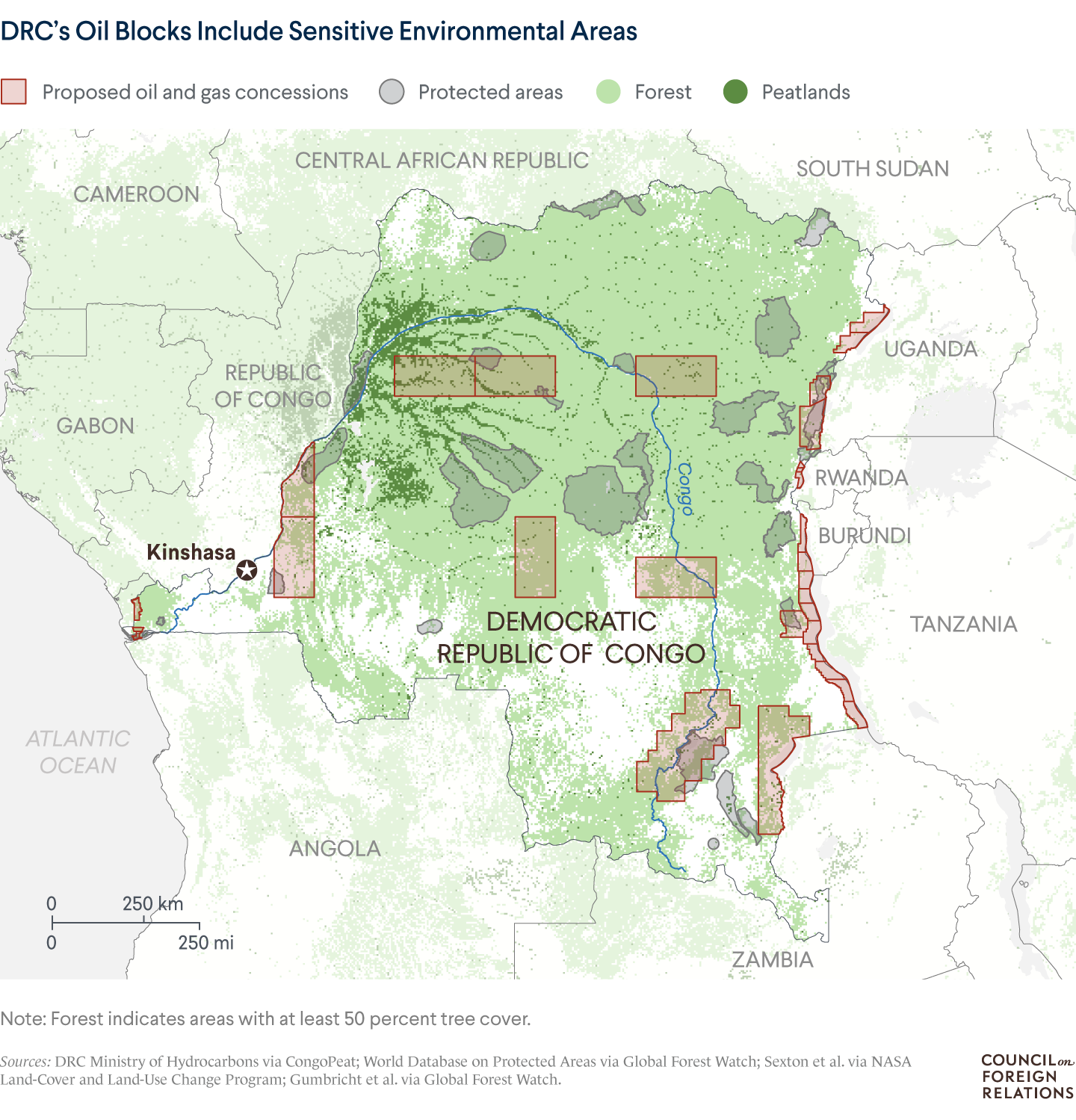

There is no dispute about the environmental sensitivity of the areas involved. The Congo Rainforest is second only to the Amazon in terms of its importance as a carbon sink. It contains the largest tropical peatlands in the world. These areas are climate superheroes, storing around twenty-nine billion tons of carbon. Exploiting these lands for resource extraction risks not only eliminating an essential tool for absorbing carbon emissions, but also drying up the peat and releasing already stored carbon into the atmosphere. (The DRC’s move also comes at a time of increasing pressure on the Amazon Rainforest.)

Biodiversity is another consideration. Of the Congo Basin’s extraordinary variety of tropical plants, 30 percent are unique to the region. Among the hundreds of species of mammals and fish and the thousand species of birds it hosts, many are endangered. Some of the auctioned blocks fall within Virunga National Park, a UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage site and home to some of the world’s last remaining mountain gorillas.

Finally, the basin plays a vital role in the hydrological cycle that drives some of the rainfall patterns in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. As droughts grow more frequent and intense in both regions—bringing heightened competition for water resources—the importance of protecting the forest will only grow more urgent.

What is the DRC’s track record on dealing with international exploitation of resources?

Congo’s natural resources and the labor of its people have been exploited for centuries. From the horrific era of Belgian King Leopold II (who in 1885 claimed much of Central Africa as his personal property and a lucrative source of rubber and ivory) through the Belgian colonial period, resource extraction from Congo almost exclusively enriched foreigners. Postindependence, the corrupt excesses of the Mobutu Sese Seko era saw a small domestic elite benefit alongside foreign partners.

And for well over two decades now, residents in eastern Congo have endured insecurity fueled in part by foreign-backed armed groups competing for access to resources. That suffering continues, even as the DRC has become a venue for increasing competition between China and the West. Despite a governance and investment climate in the DRC that often lacks transparency and emphasizes short-term windfalls over long-term development, major powers continue to seek access to Congolese minerals such as cobalt, tantalum, and lithium, which are vital for the green economy of the future.

What comes next?

The Congolese government has indicated that it received two offers for the gas blocks it auctioned, and it has yet to comment on the oil blocks. It remains to be seen whether any actual extraction will result; still, merely establishing infrastructure for oil and gas exploration will make it easier for loggers to continue deforesting the Congo Basin. The DRC has lost upward of 1.2 million hectares (roughly 4,600 square miles) of tree cover each year for the last five years, according to Global Forest Watch.

In 2021, the Congolese government pledged to develop a process for assessing the environmental impacts of basin development projects by the end of 2023. This was part of a deal to secure an additional $500 million in financing over five years to protect the basin, still only a small fraction of what experts estimate is needed. Last month, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced that the United States and the DRC will form a working group to strategize how to advance Congolese development while also protecting the basin’s forest and peatlands. Closer coordination on these issues has the potential to deepen the bilateral relationship [PDF], which has a complex history, but competing pressures could derail cooperation. The one certainty is that the DRC, like other African countries, is not going to forgo revenue-generating opportunities to protect the world from a problem it did not create without substantial compensation.

Online Store

Online Store